Skeena Reece is best-known for her critically penetrating and humourous performances, in which she portrays a range of personas that are often driven by the potential of a raw exchange with audiences. For her solo exhibition Sweetgrass and Honey, she builds on her lexicon of characters at times ramping up the clichés and emboldening stereo-types while sincerely trying to unearth their origins and stonewall their continued perpetuation. From Stockholm Syndrome to Indian Princesses, Reece uses various subjects in building a new lens with which to examine her personal history within a rereading of the displacement and continued disregard of Indigenous people in North America.

Sweetgrass and Honey is a survey of sorts, recontextualizing some of Reece’s earlier works, showing out-takes from a 2005 video An Indian Guide: Self Preservation and animating the photo shoot from We Still Know, 2007. Even the exhibition title is pulled from her debut folk music album released in 2011. This revisiting is in constant motion as a series of exposes, demonstrating Reece’s artistic processes as well as sharpening the focus on her layered but direct subject; her process being one of structured improvisation and intimate collaboration. And her subject formed by the outlines of the long, reoccurring and transmuting effects of colonization while effacing racial stereotypes used to relegate Indigenous culture into the past.

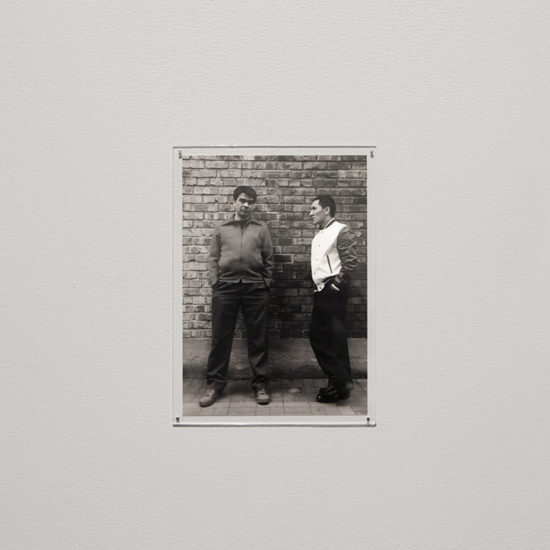

Reece often works within a narrative structure she devises to invisibly pulse under the surface of the work she produces. For We Still Know, Reece imagines a moment in the past, set in the 50s and 60s when young native men just graduating from residential schools were entering city life, looking stylish, moving with confidence and optimism, free and unencumbered. Reece posits and attempts to capture this moment, depicting a time of transition encapsulated by potential. This is an experience she imagines as her father’s, and one she knows could have only been fleeting – before the effects of racism and past traumas surfaced, at times expressing themselves in self-destructive and violent ways. But this moment of power no matter how real or sustained, is important for Reece to express as an illustration of strength and survival. This resolute and hopeful moment is the establishing shot for Sweetgrass and Honey, determining a resilient image that should linger steadfast as other narratives and exposures unfold throughout the exhibition.

The out-takes from An Indian Guide: Self Preservation express a struggle of identification, where understandings of indigeneity come into conflict with day to day experiences. At one point in the filming, Reece, who is behind the camera, asks each of the three actors how they would respond to being called a typical native man. This draws out the performers who address the multiplicity of what that description might mean as well as leads them to identify the derogatory inference of being called ‘typical’ anything. The embodiment of a typical native-ness is transformed into caricature in Entitled, 2017, a painting for which Reece commissioned the west coast painter and illustrator Collin Elder to portray her using the clichéd aesthetic devices common to paintings of the glorified Native Maiden, but her portrait sits in stark contrast to the romanticism of the Indigenous female, as she invites the voyeur to gaze upon her self-aware smirk with an air brushed double chin. Reece’s portrait has her dressed in a feather cape, posed stoically in the center of a barrage of wilderness signifiers from the wolf to the grizzly bear, but she asked for a bored wolf, a dumb spirit bear, a contentious totem pole made in the US in Haida style made by non-Haida cravers and the 2010 Vancouver Olympics inukshuk logo in a nauseating mash up of cultural clichés. She is presented as a pervasive image of the Native Indian in her natural habitat, but skewed in parody. She is an absurd dream and flawed vision of the past. Reece exacerbates this relegation to the past, by placing velvet stanchions in front of the painting as if it was in the historical section of a major museum. She further propagates this prolific image as she turns it into a mass-produced poster available for purchase in the gallery’s shop.

The past is an ever-present and fraught subject in Sweetgrass and Honey– one that Reece is constantly pushing back at and pulling into current times. In the photographic series, Un-Entitled, 2017, Reece wears “herstory” on her body. She invited the artist Gord Hill, a deeply politically charged writer and activist who is a member of the Kwakwaka’wakw nation, to illustrate aspects of colonial occupation and its destructive force, which Reece placed on her body as tattoos. Pictured on her skin are line drawings of men ready for battle. A conquistador, an Oka stand off with a Canadian soldier and an Indigenous warrior are part of her flesh. As if rising from the historic depths of battle there is also an illustration of mother and child that on the artist’s skin endure into the present, inviting viewers as caregivers to question why violence is perpetuated. Reece’s Moss Bag, 2015/17 renders this parental relation even clearer as she frees a relic from the confines of museological display. She has made an adult sized moss bag and cradleboard traditionally used as part of child rearing to carry newborns until they could walk. The sculpture, hangs on the wall like an over-sized and kitsch crucifix – a reference that shows the sacrifice of motherhood while also locating it as a place for healing and contemplation.

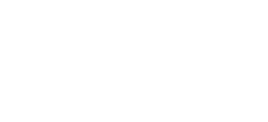

This unsettled encounter between past and present is part of We Are All One, which she first produced in response to Tsimshian Treasures an exhibition of Tsimshian ceremonial masks and objects at the University of British Columbia’s Museum of Anthropology (MOA) in 2007. Reece commissioned Vancouver-based artist Nathalee Paolinelli to paint a series of child-like black and white water-colours of some of the objects represented as artifacts in the exhibition. The humble depiction of the objects’ has an ethereal quality that reflects meaning that cannot be found in the objects themselves, but instead resonates as a cultural practice. Reece’s representations are an act of reclamation, and an acknowledgement that value is situated within the people and culture who made them and continues to produce them. A re-commissioned series of these water-colours are scattered around the exhibition as stickers on the walls. They are presented in Sweetgrass and Honey as disposable cheap renditions, again undermining their value as objects – now presented as artifacts which in MOA’s exhibition catalogue suggests were originally acquired by Reverend Robert J. Dundas as gifts or purchased for little in the mid to late 1800s, and were last auctioned off in the early 2000s by Sotherby’s for over $20,000 each, breaking records for these types of objects sold at auction. But this monetary value is not where their worth lies.

This economic schism is brought to the fore in Access Denied, a site-specific work that challenges the racialized capitalism of The Hudson’s Bay’s origins in the fur-trade. One of the company’s early flagship stores sits across the street from Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art and can be viewed through the windows of one of the institute’s gallery’s. Reece blocks the view by stacking burlap sacs from floor to ceiling. From the street, the gallery appears to be a storehouse tightly stocked full of goods. The filled room mockingly sits in opposition to The Bay in acknowledgement of Reece’s awareness of the past, and how deeply disturbing is this knowledge. This particular branch of the department store has closed three of its massive floors, amalgamating into two floors. Even with the merging of departments, the store feels barren and on the edge of closure. But Access Denied is a bluff. Once at the interior entrance to the gallery, the viewer can see that the room’s fullness is staged; it is a façade. In actuality, the gallery’s windows are only lined with stuffed sacs that sit in front of a prop wall. Even with the illusion broken, Reece denies visitors access to the gallery space. The ‘goods’ (sacs filled with air) are inaccessible – just out of reach, annunciating an economic rift that is still felt in Indigenous communities who continue to be systemically denied access to the benefits of our country including accurate historical accounting for the disabling injustices of then and now.

Reece’s challenge to historic oppression and cultural genocide is a gesture that carries consequence in that it posits a future to come. InThe Mountain Goat, a Gitksan myth, village people are punished for their poor treatment of mountain goats who they killed or harmed cruelly without reason for food. There are deadly consequences for their brutal and unreasoned actions because retribution from the mountain goats is inevitable. In cultural contrast, the mountain goats sees animals as equals to the villagers, whose moral and physical high ground implies that cruelty is dealt with swiftly and totally as they bring a mountain crashing down on the village. The new work Stekyawden Syndrome, a large-scale mural done in collaboration with Northwest Coast, Wuikinuxv and Klahoose Nations’ artist Bracken Hanuse Corlett, frames this myth within a psychological trauma that leaves captives overly sympathetic with their capturers. Reece has diagnosed Indigenous people as having Stockholm Syndrome, but this blinding condition is breaking as reprisals must be discussed.

Curated by Jenifer Papararo

Skeena Reece is a Tsimshian/Gitksan and Cree artist based on the West Coast of British Columbia. She has garnered national and international attention most notably for Raven: On the Colonial Fleet (2010) her bold installation and performance work presented as part of the celebrated group exhibition Beat Nation. Her multidisciplinary practice includes performance art, spoken word, humor, “sacred clowning,” writing, singing, songwriting, video and visual art. She studied media arts at Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design, and was the recipient of the British Columbia award for Excellence in the Arts (2012) and The Viva Award (2014). For her work on Savage (2010)in collaboration with Lisa Jackson, Reece won a Genie Award for Best Short Film, Golden Sheaf Award for Best Multicultural Film, ReelWorld Outstanding Canadian Short Film, Leo Awards for Best Actress and Best Editing. She participated in the 17th Sydney Biennale, Australia. Recent exhibitions include, The Sacred Clown & Other Strangers (2015) a solo exhibition of her performance costumes and documentation at Urban Shaman Contemporary Aboriginal Art, Winnipeg and Moss at Oboro Gallery, Montreal (2017). An iteration of Sweetgrass and Honey will travel to the Comox Valley Art Gallery.

Parts of Sweetgrass and Honey were produced in collaboration with Oboro, Montreal and exhibited as part of the exhibition Moss.

LIST OF WORKS: All works by Skeena Reece

*Many of the artworks presented in this solo exhibition were produced in collaboration with other artists who Reece ignites as producers & translators.

We Still Know, 2007 / 2017 (animation of digital photographs; 35 min)

I’m Telling You, 2007 / 2017 (digital print; 5 x 7 in). From the digital photo series: We Still Know, 2007

Moss Bag, 2015-17 (fabric, cedar, moss; 3 x 8 ft)

Un-Entitled, 2017 (four digital photographs; commissioned drawings by Gord Hill; 36 x 36 in)

Entitled, 2017 (commissioned oil painting by Collin Elder; 31 x 50 in (framed)); also limited edition print. 24.75 x 39 in

We Are All One; Actually These are All Mine, 2018 (printed vinyl stickers; commissioned watercolor by Nathalee Paolinelli; various sizes). From the performance: We Are All One, 2008 in response to the exhibitionTreasures of Tsimshian People at University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology

Stekyawden Syndrome, 2018 (commissioned painted mural by Bracken Hanuse Corlett; 32 x 10 ft)

Access Denied, 2018 (burlap sacs, plastic, air and wood; site-specific installation in Plug In ICA’s Richardson Foundation Gallery)